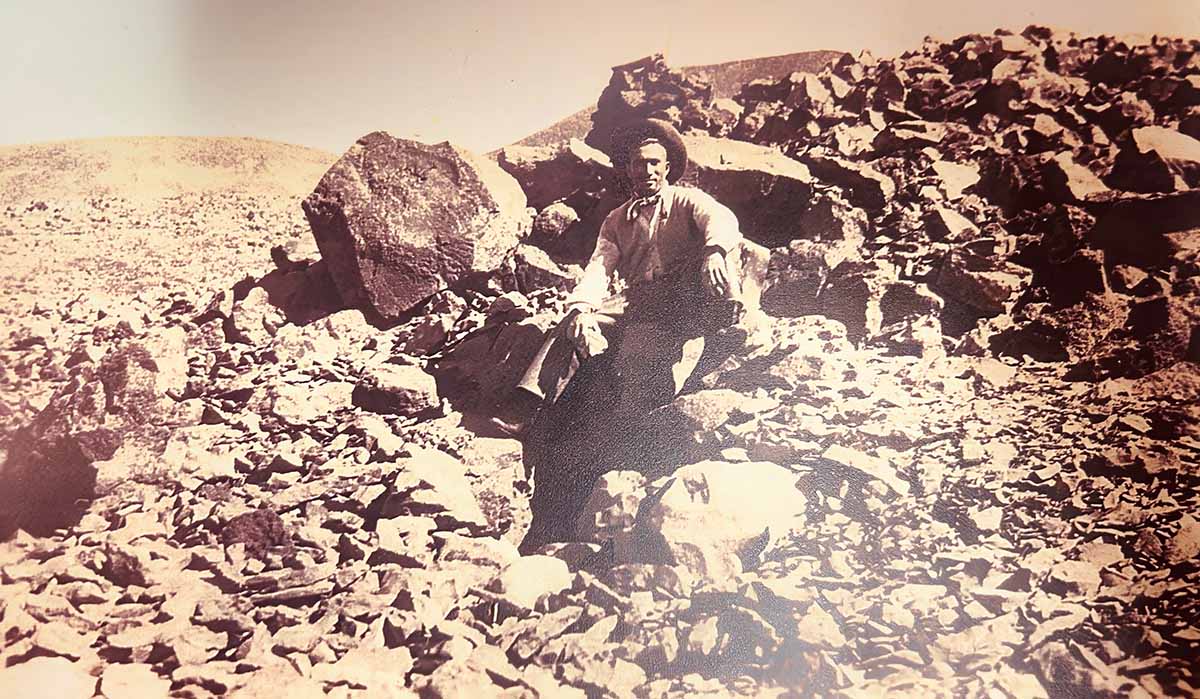

Willy Kaniho at the Mauna Kea Adze Quarry in 1926

Before Horses: Hawaiʻi Craftsmanship

Long before the first horse set hoof on Hawaiian soil, Native Hawaiians were already master craftspeople working with some of the hardest materials on earth. The Mauna Kea Adz Quarry was the largest primitive rock quarry in the world and was used by the ancient Hawaiians to both obtain basalt and make various stone tools. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the quarry was being used by 1000 A.D. with more intensive use after 1400 A.D.[1]

Native Hawaiians established standardization in adze making, suggesting that different people specialized in the various aspects of adze manufacturing at the site, and were experts in their craft.[1] This tradition of specialized craftsmanship reflects the broader Hawaiian cultural practice of developing expert skills suited to local materials and conditions—an adaptability that continues to serve paniolo well in many aspects of ranch life.

Arrival of Horses: Paniolo Culture Beginnings (1792-1832)

According to Dr. Billy Bergin, founder of the Paniolo Preservation Society, cattle first arrived in Hawaiʻi in 1792 as a gift from British Captain George Vancouver to King Kamehameha I. The cattle multiplied rapidly under a protective kapu (prohibition), eventually decimating taro crops needed to feed the kingdom.[2] To manage these wild cattle, horses became essential. In 1803, an American trader from Salem, Massachusetts, Richard Cleveland, brought the first horses to Hawaiʻi and presented them to King Kamehameha I.[4] However, it would take several more decades before skilled horsemen arrived to teach Hawaiians how to use these animals effectively for cattle work.

In 1832, King Kamehameha III invited three Mexican vaqueros from Mexico to teach Hawaiians cattle-handling skills and horsemanship.[3][4]

Paniolo William Kealoha

With horses came the immediate need for farrier work. While the earliest farriers serving the royal horses remain undocumented, by 1850 Charles Cockett had established a blacksmith facility in Lahaina.[5] Working at his forge with anvil, tongs, and hammer, Cockett crafted horseshoes along with spurs, bits, branding irons, and various tools essential to ranching operations. As Dr. Bergin notes, horseshoes typically last only about one month in Hawaiʻi’s demanding conditions before requiring replacement.[2]

Early Days: Parker Ranch Blacksmith Shops

From Parker Ranch‘s earliest days in Mānā, blacksmith services were essential to ranch operations. By 1850, a blacksmith shop was shoeing the ranch’s horses, mules, and draft animals. The farrier’s workspace centered around a wood-fired forge, with essential tools—files, nippers, and hoof knives—within easy reach of a hip-high anvil mounted on a sturdy kiawe wood base. Bellows maintained the fire needed to heat iron for shaping.[5]

As Parker Ranch expanded its operations and land holdings, blacksmith facilities grew to meet increasing demands. By the early 1900s, ranch operations extended into the fertile Waikiʻi area where farming required heavy equipment maintenance. While the Waimea headquarters continued providing blacksmith services, Waikiʻi developed its own substantial facility by 1910 to support agricultural machinery, tractor maintenance, and the care of heavy draft horses used for hauling equipment and crops.[5]

The Evolution of Farrier Work in Hawaiʻi

For much of paniolo history, specialized farrier services were uncommon. Dr. Tim Richards, respected Hawaiʻi State Senator for Senate District 4 and local veterinarian explains that in earlier times, cowboys handled their own horseshoeing needs. Ranch blacksmith shops maintained forges where they “would forge their own shoes here,” a practice that continued through the 1940s and into the 1950s. According to Dr. Richards, “probably the 40s to the 50s is when they stopped using the forge because the farrier shop was there.”[7] Professional farrier services only became widely established in Hawaiʻi within the last 25 to 30 years, marking a significant shift from the self-sufficient cowboy tradition.[7]

Challenging Island Terrain

Hawaiʻi’s volcanic landscape presented extraordinary challenges for both horses and farriers. Dr. Bergin explains that some ranchers experimented with raising young horses without shoes, turning them out on lava fields and rough terrain to naturally toughen their hooves. However, most working horses require regular shoeing to handle the demanding conditions.[2]

Rugged Volcanic Terrain

The harsh reality of paniolo work became dramatically visible when shod horses galloped across rough aʻa or pahoehoe lava—sparks fly from the contact between iron shoes and volcanic rock, and make a very distinctive sound. Additionally, horses fare better in the drier, leeward parts of the islands but require special hoof care in the wetter windward areas where constant moisture presented different challenges.[2]

Road Systems: Transformations

The development of Hawaiʻi’s road system would surely have impacted the demand for farrier services. In the early days of paniolo work, travel was primarily overland on trails. Paved streets were unknown until 1881. In that year, Honolulu saw some of the first efforts at street paving.[6] On the Big Island, roads developed much more slowly.

This slow transition from trails to gravel roads to paved highways meant that for most of paniolo history—from the 1830s well into the mid-20th century—horses worked primarily on unpaved surfaces. The rough volcanic terrain, combined with dirt and gravel roads, created constant demand for skilled farriers who could keep working horses shod and healthy. Though automobiles have become norm in Hawai’i’s urban areas and throughout the islands, Hawaiʻi’s ranch horses will always need regular farrier care.

Typical spare horseshoe case

Multicultural Tradition: Immigrant Blacksmiths

Hawaiʻi’s ranching industry attracted skilled craftsmen from around the world. Russian and German immigrants brought valuable blacksmithing and harness-making expertise, and these experienced smiths were eventually recruited to establish a central blacksmith facility near the Pukalani Stables complex southeast of Waimea village.[5]

Duke Karimoto: Master Farrier and Innovator

Perhaps no farrier better exemplifies the multicultural nature of paniolo craftsmanship than Duke Karimoto. Born in Hāwī, Hawaiʻi, Karimoto became head blacksmith at Puakea Plantation in Kohala in 1926. This plantation was later acquired by Parker Ranch. In 1941, ranch manager A.W. Carter brought Karimoto to Waimea to serve as Parker Ranch’s blacksmith. [5]

At Parker Ranch, Duke’s responsibilities extended beyond traditional farrier work to include fabricating a wide range of ranch equipment—branding irons, gate hardware, hinges, bolts, wagon wheel rims, and door latches. During World War II, when metal became scarce, he demonstrated exceptional skill in recycling and repurposing available materials to keep ranch operations running. He also trained the next generation of blacksmiths who became skilled journeymen under his tutelage. Duke Karimoto retired from Parker Ranch in 1964, as the ranch’s operations were beginning to modernize.[5]

New Tech, Same Challenges

The tradition of paniolo farrier work continues into the present day, adapting to new technologies while honoring time-tested methods. Today’s farriers face the same volcanic terrain and humid conditions their predecessors did, but with modern materials and techniques.

Remembering Clifford Lorenzo

The paniolo community recently lost one of its respected farriers. Clifford Lorenzo of Waimea passed away in October, 2025. He was the son of paniolo and Paniolo Hall of Fame inductee Arthur Antone Lorenzo, and carried on his family’s traditions of ranching and horseshoeing.

Dr. Tim Richards knew Lorenzo personally for many years, and recalled his skill and approach: “He was a modern farrier, but he had the old style… He tried to adapt to the horse’s needs so that they would be exceedingly tolerant.”[7]

Lorenzo was well-respected in the ranching community for his skill in handling difficult horses and his craftsmanship in shoeing. Dr. Richards was among those who relied on his expertise for their horses.

Clifford Lorenzo exemplified the enduring paniolo farrier tradition—combining technical skill with patience and respect for the animals in his care. His work connected generations of Hawaiian cowboys, from his father’s era at Parker Ranch to today’s working ranches across the islands.

Preserving the Tradition

From ancient stone tool makers to modern farriers, Hawaiʻi’s tradition of specialized craftsmanship has adapted to serve each generation’s needs. Today’s paniolo farriers carry forward this legacy, maintaining the essential skills that keep working horses sound on the islands’ ranches.

References

[1] National Park Service. “Mauna Kea Adz Quarry.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/places/mauna-kea-adz-quarry.htm.

[2] Bergin, Billy. Personal communication. 28 October 2025.

[3] “Aloha Vaqueros Exhibit Honors Mexican and Hawaiian Traditions.” KENS5, https://www.kens5.com/article/news/local/aloha-vaqueros-honors-connection-hawaii-mexico-briscoe/.

[4] Yabumoto, Michelle. “Two Centuries Ago, 3 Californians Crossed an Ocean and Changed Hawaii Forever.” SFGATE, 21 January 2024, https://www.sfgate.com/hawaii/article/hawaii-cowboy-paniolo-history-18615187.php.

[5] Paniolo Preservation Society. https://paniolopreservation.org

[6] “Evolution of Ancient Trails to Roads and Streets.” Images of Old Hawaiʻi, 8 January 2022, https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/evolution-of-ancient-trails-to-roads-and-streets/.

[7] Richards, Tim. Personal communication. 28 October 2025.

Additional Resources

Bergin, Billy. Loyal to the Land: The Legendary Parker Ranch, 750-1950. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8248-2692-2.

This article is dedicated to preserving the memory and skills of Hawaiʻi’s paniolo farriers, past and present.

This article is dedicated to preserving the memory and skills of Hawaiʻi’s paniolo farriers, past and present.