Paniolo Preservation Society is a state-wide organization, and we proudly celebrate cowboys and cowgirls on all the islands. Their legacy is part of the rich paniolo culture that continues to thrive today. On Kaua‘i, where fresh water is plentiful, ranching came naturally—and stayed long after the sugar cane industry turned sour.

In researching Kauai’s paniolo history, we came across some unexpected things.

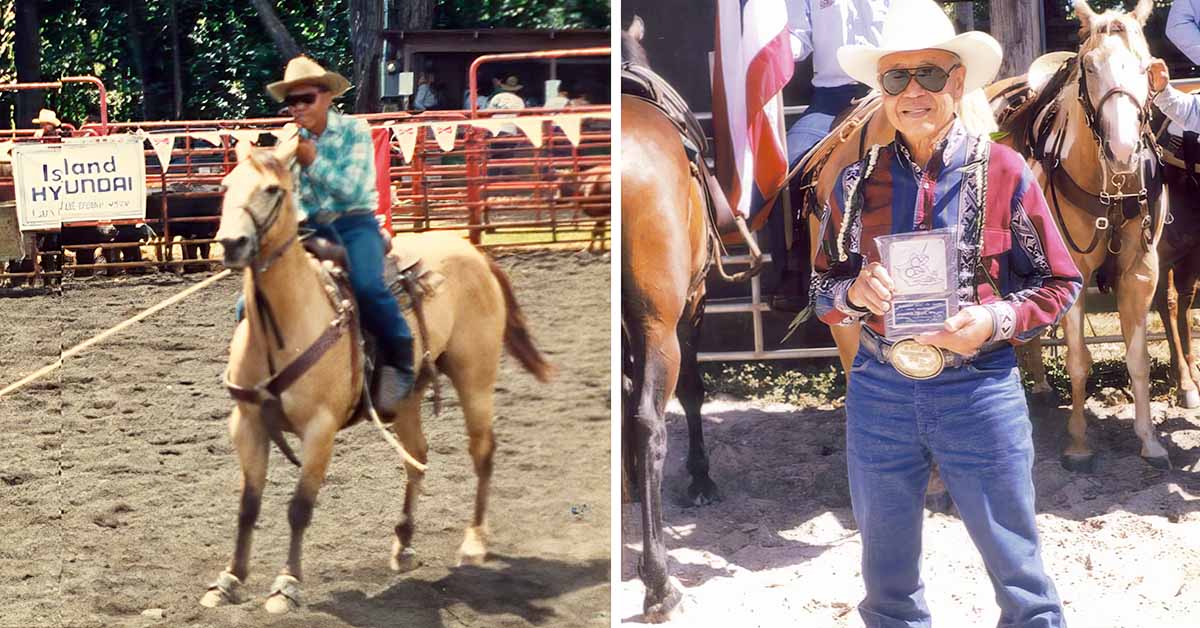

For example, Kaua‘i cowboy Harold Sung Wa Aiu, Paniolo Hall of Fame Class of 1999, ran his own ranch for 25+years, and was a rodeo champ until he was almost 80. But one of his first memories is helping his grandparents till the rice paddies, and tending to the water buffalo.

Harold Sung Wai Aiu

“Most people, that’s what they used, because those water-buffalos could go into the mud and pull a plow, whereas horses wouldn’t be able to,” he said in his Oral History. “They’re huge animals, big horns, but they were tame, and they were tied with a ring around their nose so they wouldn’t fight the rope. Because, if you put a rope around their neck, well their neck is so strong that they just—you know, like a rhino or something, very strong. But with a ring around their nose, they become very docile. So that’s how it was, and you strap a plow behind them, or a harrow, and went into the water.”

In 2000, Eddie Taniguchi, Sr., and his son Eddie Taniguchi, Jr. were both inducted into the Paniolo Hall of Fame. Junior wasn’t expected to be a paniolo, after a horse kicked him in the face. He was only 9 years old but got right back in the proverbial saddle, and went on to become a great horseman. But if Junior was great, Senior was a master.

“I was in Honolulu when he died, and we had a phone call that his horse wasn’t eating,” Eddie Junior remembered in his Oral History. “So when we came home I told my mom, and my sister, you know, ‘only way we’re going to get the horse out of that is, gotta bring it to the funeral. They said, oh, how we going to do it? Put all his things on him, his saddle, like he going to ride him. Saddle him up. Put it on the trailer, bring him to the grave. . .’

Eddie Taniguchi Jr. with granddaughter. Photo credit: Brian C Howell.

“So just before the casket went down, I made the sign to bring the stallion. So he brought him. When he came, he came tearing—luckily he had a long rope on him. Tearing—he almost got in the hole! He went right to the edge of the hole; dirt was flying on the casket. He wanted to grab the casket, grab his hat and all that. Then he started rearing and screaming, until the thing hit the ground. Took away the horse, put him back in the trailer. While he was walking away, he would turn around, scream and yell at, you know. We put him on the trailer, he looked from there, and he starts crying. Took him home, and after that he was alright. That was—that was something that—nobody believed that, you know.”

David “Duke” Wellington

After fleeing from Europe ahead of the Nazis, Duke served in Korea—twice—and then became an American citizen. He went to college to study Animal Science and roomed with some young men from the Big Island who encouraged him to go there, but he ended up finding work on Kaua‘i.

At the end of the sugar cane era, an opportunity came for Duke to buy former plantation land, and he was able to qualify for a special grant if he hired former sugar workers. Duke got the land, christened it the Rocking W Ranch, and started buying cows until he hit 200 head.

Decades later, when Duke’s son Stewart got involved with the ranch, he decided to diversify—bringing in something unusual for Kaua‘i ranches: American bison. Under the name Hanalei Bison Ranch, the operation ran both bison and cattle, keeping the herds separate because of their different needs, speeds, and “personalities.” (For example, if you herd bison to a gate, and then push them too hard, they are just as likely to turn around and come back at you, as they are to go through.)

In 2021, Hanalei Bison Ranch, marketed as a high end luxury property, was sold (animals and all) to American architect Richard Meier and his family for $32 million.

Sharleen Andrade Balmores is a sixth-generation Kaua‘i rancher, who has harnessed the internet to market her family’s quality beef. Farmer’s Daughter Reserve features local grass-fed beef, carefully raised until mature enough to have developed the ideal musculature with the right amount of marbling and fat.

As she wrote in her blog, “. . . Tending to your herd is much like meticulously caring for your garden.

Raising animals with care until they reach full maturity makes all the difference. We believe that when you care for the land and its animals, it, in turn, takes care of you. Nature doesn’t rush, and neither do we. It’s about honoring the seasons, respecting time, and embracing what’s ready to harvest.”

Rancher’s Daughter Reserve steaks are dry-aged, a slow process where half-carcasses are hung in a temperature controlled environment and salted with Hawaiian salt for 28-45 days. This lets natural enzymes break down the muscles gradually, for a more tender and juicier steak. Sharleen has also created a line of skin products and candles made from tallow.

Enterprising, determined, creative and unafraid, the paniolo of Kaua‘i braid together the stories of their ‘ohana over many generations, binding them fast into Hawaii’s paniolo legacy.